By: James Gregg

As both a frequent traveler and Zen practitioner, I was very happy to recently spend 2 weeks in Japan with my family.

Not only did we do the “tourist” thing, soaking in the uniquely Japanese experience, I also got a rare opportunity to touch the literal roots of our shared practice and lineage.

My first stop was to Daihonzan Sojiji, one of the two head temples of Soto Zen in Japan, and the place where our dharma great-great-grandmother Roshi Jiyu Kennett trained with Keido Chisan.

This temple is located in Yokohama, a short train ride south of the main metropolis of Tokyo.

I was only able to spend half a day here, but during that time was able to sit zazen and offer incense in the main Dharma hall, and I was able to see the wood-carved calligraphy by Keido Chisan over the door to the Butsuden.

As I walked towards the Sodo (the monk’s hall), I heard the sound of the bell ringing, and was able to listen outside the door as the monks performed a short chanting service, and then went silent, most likely practicing zazen. It was comforting and wonderful to sit nearby as the monks went about their communal practice.

My next stop was in Fukui Prefecture, almost due west of Tokyo near the Sea of Japan, and an hour north of Kyoto.

Fukui is home to Eiheiji, the other head temple of Soto Zen, and the monastery established by Dogen Zenji in 1244 after he left Kyoto.

This monastery is where some of the later fascicles in the Shobogenzo were written, and where most of the sermons recorded in the Eihei-Koroku (Dogen’s Extensive Record) were given. It was also Dogen’s final monastery, as he passed away during his tenure here.

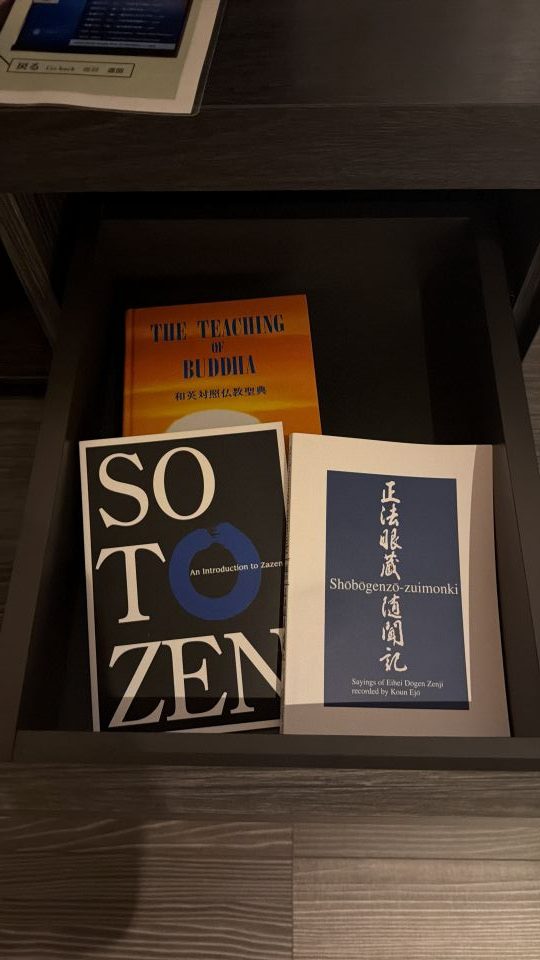

We stayed 2 nights at Hakujukan, a hotel owned and operated by the monastery – where else will you see Dogen Zenji’s portrait hanging over the reception desk? Instead of the Gideon Bibles we’re used to in American hotel rooms, our rooms were furnished with copies of Dogen’s “Zuimonki” and a treatise on Zen Buddhism, which were free to take! The chef overseeing the restaurant’s menu was also the monastery’s head tenzo, so the meals we had there bore much resemblance to what the monk’s eat (albeit somewhat fancier).

Both mornings that I was there, I was invited to participate in the monks’ morning chanting service.

I arose at 4:00am and, along with a few other guests, met with a representative of the monastery in the hotel lobby. We trekked 100 yards in the dark to the visitor entrance of Eiheiji, where we were turned over to one of the monks. He led us up multiple flights of stairs (300 in all, I believe) to the “Hatto,” the highest building in the monastery and the primary Dharma hall.

Once we were seated, the monks began to appear, silently filing into the room, taking their places on the vast tatami floor. I was surprised to see that the monks sat seiza (kneeling, sitting on their heels) directly on the tatami – no zafus or zabutons here! Most of the monks wore the standard black robes, while a smaller group also wore beige okesas that indicated teacher status. A monk stood in a large window that was cut out of one wall, intermittently striking a large bell. After a few minutes, a small group of monks appeared, one of whom was holding an “inkin” bell (the same type we use for kinhin and our Three Full Bows), performing a call-and-response with the larger bell.

Finally, one of the vice abbotts appeared in a splendid bright orange robe and embroidered okesa. He performed 3 bows at the haishiki (bowing mat), and offered incense to the large Buddha statue in the butsudan. As the monks began chanting, we were instructed to stand up, make gassho and approach the butsudan, where we were allowed to offer incense as well. I cannot begin to explain how it felt to be standing in Dogen’s monastery, walking past chanting monks, offering incense at the amazing and elaborate butsudan!

It was at this point that I realized the woman sitting next to me was wearing a rakusu and was performing the 3 Bows and making gassho at all the right times – in talking to her later, she said she was from France, and a student at one of the zendos affiliated with the Association Zen Internationale, a Zen organization founded by Taisen Deshimaru, a disciple of Kodo Sawaki.

Chanting service then began – we chanted the “Sandokai” (Harmony of Difference and Sameness, but in Japanese) and both the “Shosai Myokichijo Dharani” and the “Daishin Dharani,” exactly the same as we do them at Bright Way. The choreography of simple acts such as distributing chant books and placing instruments, the attention to detail and care that was taken, was inspiring.

Once chanting service concluded, a few of the monks took us on a brief tour of the Butsudan (Buddha Hall), where they showed us statues of the 3 times of Buddha – past, present, and future – and the largest mokugyo drum and kesu bell I’ve ever seen. They then took us to the Sanmon, or “mountain gate,” the gate that aspiring mendicants approach when they wish to enter the monastery to train. Along one pillar of the gate was a board into which was carved a phrase that basically said “training here is very difficult, go away if you can’t handle it!” 🙂

We also visited the Joyoden, the hall containing a large black urn containing the ashes of Dogen Zenji, as well as the ashes of many of the later abbotts of the monastery.

Later in the day, we met again at the entrance to the monastery, and proceeded up to the 2nd floor of the main administrative building, where they have a special Sodo (meditation hall) designed for guests. This room has the same raised tatami platforms on which junior monks sleep, eat, and do zazen in the main Sodo. We received basic zazen instruction from one of the monks (which, of course, followed the edicts laid down by Dogen in “Fukanzazengi” and other treatises), and then sat zazen for about 20 minutes.

Obviously, I wasn’t able to get photos of either of these events, but I did return later in the day to get a photo of the Hatto where chanting service had taken place.

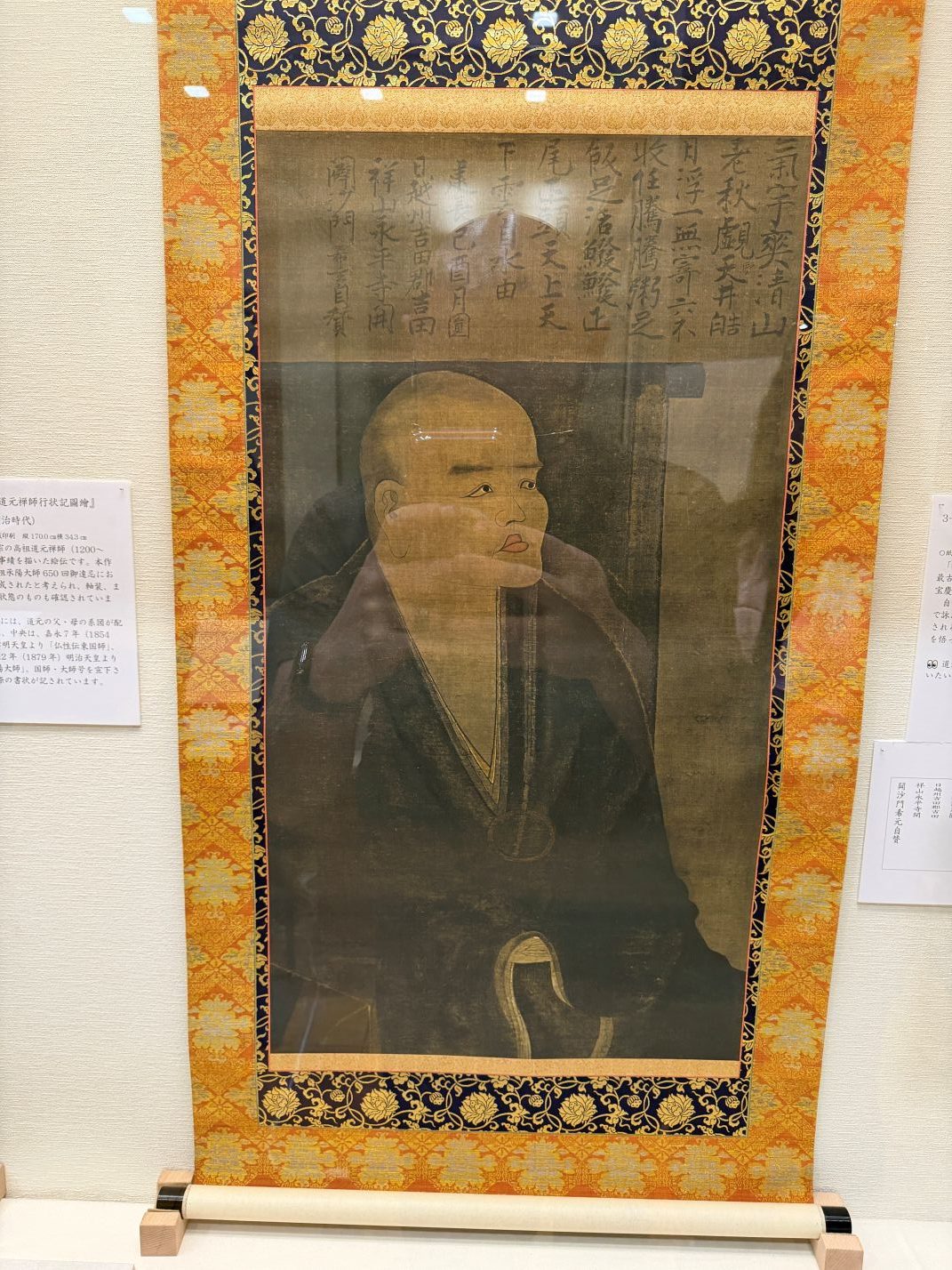

Afterwards, I visited the Eiheiji museum, which contained multiple artifacts from Dogen Zenji’s time. The most impressive of these was a large scroll containing the text of “Fukanzazengi,” brushed by Dogen Zenji himself in 1233, when he was still in Kyoto. This date and placement makes it one of the earliest copies of the text. To see ink on paper and know that it was placed there by Dogen’s hand was an inspiring moment – so often it’s easy to forget that these teachings came from actual human beings who had struggled with their own karma and managed to break through and realize the Way for themselves. Seeing physical evidence of their existence helped to confirm that we, too, are capable of awakening!

Finally, we traveled to Kyoto, where I was able to visit Daitoku-ji, the famed Rinzai Zen monastery famous for its gardens, and where seminal Zen figure Ruth Fuller Sasaki practiced and conducted research that was invaluable to some of the earliest translations of Zen texts into English.

Outside of my actual interactions with Buddhism and Zen – of which there were many more than I can recount here – the entire culture was obviously permeated with the spirit of Buddhadharma and Shinto practice: the respect for humility, respect, and quietude is evident even on the busy streets of Tokyo.